An alphabetic writing system is a code for converting the sounds of speech into text. For example the sounds /b/ /a/ /t/ can be coded as ‘bat’. Spelling is a two-way code, a skilled writer can encode the sounds into a string of letters, and a skilled reader can subsequently decode them. The skills required are mapping, segmenting, and blending, and together we call these skills ‘phonics’.

If only teaching your child to read was that simple. There’s a lot more to reading and spelling, especially in English. But stick with me, because the ideas in that opening sentence are really, really important.

The key idea I want you to hold is that there are sounds of speech (“phonemes”), text representations (“graphemes”), and a reversible mapping between them called the spelling system.

English is Particularly Hard

Spoken English has between 35 and 45 sounds, depending on who is counting and why. Most English phonics programs settle on around 40 sounds. Examples of these sounds are the five ‘short vowels’ (/ah/ as in Apple, /eh/ as in Egg, /ih/ as in Igloo, /aw/ as in Otter, and /uh/ as in Umbrella).

Different languages have different phonemes. For example, there is no English equivalent to the guttural Russian /ch/ or /kh/ sounds which seem to need clearing your throat in mid-word. More importantly, languages have different NUMBERS of phonemes. Italian has a modest 30-32 different sounds, while Standard German has 70-75 sounds.

Written English uses an alphabet of 26 letters to represent the 40 standard sounds, not quite enough, so we need to add some tricks to our spelling system. Europeans mostly use the same alphabet, but often add accents to extend it, even the Italians with their paltry 32 sounds use accents to create a very simple, predictable mapping.

If I taught you how to pronounce the various German letters and accents, and gave you a German newspaper to read aloud, you might not understand a word but a German-speaker passing by would understand what you were saying. That’s not possible in English where there is no clue in the coding that ‘healer’ and ‘health’ are pronounced so differently.

We Don’t Read with Phonics

Phonics is controversial because skilled readers mostly do not use it; phonics is simply a stepping stone for learning to read. You may have been taught rules or mappings of phonics as a child, but as a skilled reader you no longer refer to them. Most of us could not name the 40 sounds of English, or recall any of the basic ‘Rules of English Spelling’.

Perhaps we were not even taught phonics, so we might imagine that phonics was optional. Steven Strauss wrote a devastating critique of phonics where he identified several fatal flaws in the ‘necessity’ of phonics – in particular that many ordinary words need to be identified before the mechanics of phonics can be used to decode them.

Perhaps we were not even taught phonics, so we might imagine that phonics was optional. Steven Strauss wrote a devastating critique of phonics where he identified several fatal flaws in the ‘necessity’ of phonics – in particular that many ordinary words need to be identified before the mechanics of phonics can be used to decode them.

This blog post won’t go there, but let me assure you. You absolutely, definitely know the 40 sounds of English. You could not speak or listen without knowing them. You could not read or spell without knowing the basic rules of spelling. Perhaps not all of them, it would take about 2,000 rules to turn written English into sounds, but certainly the basic dozen or so. You just aren’t aware that you know them.

Strauss is probably right that most students don’t need explicit phonics instruction. But our concern is students who struggle with reading, those who have not developed the skilled decoding and encoding required for strong reading. For your child, phonics is non-negotiable.

But What Kind of Phonics

The Torgesen study compared two different kinds of phonics, and found both equally effective. But don’t be mislead into thinking that all phonics programs are equal. Torgesen compared two effective programs, there are many phonics programs that are useless, and others that can actually hurt your child.

Broadly speaking, there are four main styles of phonics programs, ‘Synthetic Phonics’, ‘Visual Phonics’, ‘Analytical Phonics’, and ‘Junk Phonics’. A specific program may include bits from different types of phonics, but that’s usually not a good sign. Let’s look at the four types of phonics.

Synthetic Phonics

The idea of synthetic phonics is simple – if there are 40 sounds in English, then create a ‘synthetic’ alphabet with 40 special characters to teach it. With those 40 icons or codes representing the sounds, we can investigate the mappings of the sound-to-spelling mappings in a simple way, attaching different spellings to each sound.

The best synthetic phonics program that I am aware of is Phono-Graphix, which uses the most common spelling of a sound as the ‘key’ to the synthetic alphabet. Below are the 15 vowels taught by Phono-Graphix. The sound with the key ‘oo’ (top right corner) has nine common spellings, with an example of each.

Phono-Graphix is a complete phonics program, it teaches the basic spellings and also the ‘advance code’ of roughly 200 common alternate spellings. Many synthetic phonics programs only teach the most basic spellings or a small subset of the common alternate spellings. The free BLENDING program on this website is largely based on the ideas in Phono-Graphix.

‘Jolly Phonics’ is another well-known synthetic phonics program. It uses hand signals (for example /s/ is coded by a slithering movement with the hand, and representing a snake). This makes Jolly Phonics particularly well-suited for classrooms, since the teacher can visually determine whether each student correctly identifies the sounds in an exercise by their hand movements. Jolly Phonics is ‘incomplete’, it provides almost no support for the advanced code.

WARNING: Jolly Phonics has some serious design flaws (we explain here) and you should not consider it for any struggling reader. If your child struggles with reading in a school that uses Jolly Phonics, then immediately start working with him at home with a different program.

There are many other excellent synthetic phonics program, including “See the Sound” (the ‘sun’ image) which seems particularly effective with deaf students, and Lindamood-Bell’s ferociously expensive LiPS intervention program ($20,000 and up, but worth every cent).

There are many other excellent synthetic phonics program, including “See the Sound” (the ‘sun’ image) which seems particularly effective with deaf students, and Lindamood-Bell’s ferociously expensive LiPS intervention program ($20,000 and up, but worth every cent).

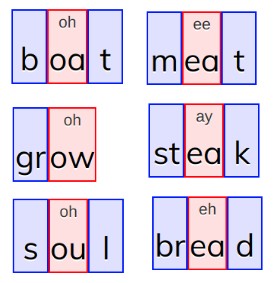

One of the features of a Synthetic Phonics program is that there are no ‘rules of phonics’ to be memorised. The vowel in the words ‘boat’, ‘grow’, and ‘soul’ share the same single sound /oh/ but map to three different spellings. The words ‘meat’, ‘steak’, and ‘bread’ have three different sounds that map to the same spelling. You won’t ever see a rule like “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking” because the concept of “two vowels” is alien to this flavor of phonics.

One of the features of a Synthetic Phonics program is that there are no ‘rules of phonics’ to be memorised. The vowel in the words ‘boat’, ‘grow’, and ‘soul’ share the same single sound /oh/ but map to three different spellings. The words ‘meat’, ‘steak’, and ‘bread’ have three different sounds that map to the same spelling. You won’t ever see a rule like “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking” because the concept of “two vowels” is alien to this flavor of phonics.

Visual Phonics

There is an ugly brother of Synthetic Phonics called ‘Visual Phonics’. It teaches the same spelling to sound mappings, but starts with the spellings and move to the sounds. Most Orton-Gillingham (O-G) programs use this approach, for example Barton.

The short versions of Visual Phonics teach the 26 “sounds” of the 26 letters of the alphabet, which is useless.

The longer version starts with the common 250 or so letters, digraphs, and phonograms, and teaches their sounds. For example, there are nine different spellings that happen to make the sound /ay/ (‘ay’ as in ‘hay’, ‘ai’ as in ‘train’, ‘ea’ as in ‘steak’, and six others). This is valid, but it is the hardest imaginable way to teach, and the student likely remains baffled when encounters the sound /ay/. Researchers suggest that the Visual Phonics approach overloads the child’s memory.

The longer version starts with the common 250 or so letters, digraphs, and phonograms, and teaches their sounds. For example, there are nine different spellings that happen to make the sound /ay/ (‘ay’ as in ‘hay’, ‘ai’ as in ‘train’, ‘ea’ as in ‘steak’, and six others). This is valid, but it is the hardest imaginable way to teach, and the student likely remains baffled when encounters the sound /ay/. Researchers suggest that the Visual Phonics approach overloads the child’s memory.

Synthetic Phonics would teach exactly the same mappings, but organized differently to starts with the single sound /ay/ sound and then teach its nine spellings. It’s conceptually simpler. Perhaps the child will make some spelling errors, but the words will be phonetically understandable.

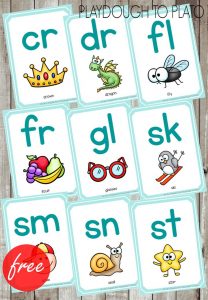

As well, Visual Phonics programs often try to teach different sound-units with the same methods, for example teaching phonemes, chunks (‘bl-‘ or ‘-st’), and even whole syllables. This complicated and muddled approach probably accounts for why O-G tutoring can bang on for years without noticeable improvement in the student’s reading.

As well, Visual Phonics programs often try to teach different sound-units with the same methods, for example teaching phonemes, chunks (‘bl-‘ or ‘-st’), and even whole syllables. This complicated and muddled approach probably accounts for why O-G tutoring can bang on for years without noticeable improvement in the student’s reading.

One of the problems with a complex approach like this is that tutors get anxious and start to take shortcuts, for example adding the rules of Analytical Phonics. Many of the shoddier O-G programs actually include those rules.

Analytical Phonics

Analytical or ‘Embedded’ Phonics tries to ease students into phonemes by finding the phonics in eclectic sources such as whole-language levelled readers and memorised lists of sight-words. Typically the ‘phonics’ lessons move from bigger chunks to smaller; starting with whole words, then word families and blends, then individual phonemes.

As Diane McGuinness points out, “This is tantamount to teaching three different writing systems one after the other, each cancelling out the one before.” That’s probably the most polite thing you can say about this kind of phonics.

A key idea in Analytic Phonics is to NEVER to pronounce a sound in isolation. Instead a set of words with a shared phoneme is presented (for example ‘big’, ‘bat’, ‘bush’ and ‘ball’), and students discuss how they are alike or different, hopefully inferring the underlying code.

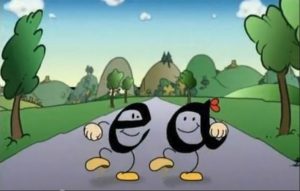

It is in this flavor of phonics that you find the ‘rules’ of phonics – for example “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.” (suggesting that a digraph vowel like ‘ea’ should be mapped to the sound /ee/). These rules are often celebrated in songs, drawings, and videos. Program authors are unfazed that these ‘rules’ are wrong almost half the time, correct for ‘meat’ but wrong for ‘steak’ and ‘bread’. It should be horrifying enough that a student is being told there are ‘two vowels’.

It is in this flavor of phonics that you find the ‘rules’ of phonics – for example “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.” (suggesting that a digraph vowel like ‘ea’ should be mapped to the sound /ee/). These rules are often celebrated in songs, drawings, and videos. Program authors are unfazed that these ‘rules’ are wrong almost half the time, correct for ‘meat’ but wrong for ‘steak’ and ‘bread’. It should be horrifying enough that a student is being told there are ‘two vowels’.

Not surprisingly, Analytic Phonics programs are disorganised and inconsistent, and most should be downgraded in the category of Junk Phonics.

The spelling posters in your child’s classroom are probably from this flavor of phonics. Teachers buy them from school supply houses (or get them free from publishers) and put them up as decorations.

Junk Phonics

‘Junk’ is a polite word for the flavor of phonics that would be better not taught at all. But it’s not just a dumping ground for well-meaning-but-ignorant phonics programs. There is actually an intentional design category for Junk Phonics.

School curriculums that use basel-readers or ‘reading books’ are mostly in this category. Basel-readers are the foundation of ‘Whole Language’ instruction favored by many school boards, and phonics is intentionally avoided or only taught indirectly in those classrooms.

Basel-readers provide sequenced lessons for groups of students to follow, with stories and comprehension exercises, assessments, controlled vocabulary, and a matching teacher’s version with lesson plans. The level of difficulty increases as the student moves through a series of books and new concepts are gradually introduced.

Basel-readers provide sequenced lessons for groups of students to follow, with stories and comprehension exercises, assessments, controlled vocabulary, and a matching teacher’s version with lesson plans. The level of difficulty increases as the student moves through a series of books and new concepts are gradually introduced.

The phonics components, if any, is not intended to help students become readers. Phonics instruction in these books is secondary to the story progression, so it is not surprising there is no systematic instruction of sound-to-spelling mapping. Often there is a disproportionate effort to teach a specific spelling pattern required for the next story. Misinformation and inconsistencies are common.

This is likely how your child’s classroom is teaching him to read. Hard to believe? Here’s a grim report by the Center for the Study of Reading at the University of Illinois.

Teachers love these basel-readers because they closely follow the academic standards required by the school boards. Publishers love to sell them. But they are bland and offer no interest or challenge. Students find them tedious and boring.

Toe-by-Toe

Many readers of this blog use the excellent Toe-by-Toe (TbT) phonics program, especially in Northern Ireland where Jolly Phonics is widely used in schools and reading failure is common.

Many readers of this blog use the excellent Toe-by-Toe (TbT) phonics program, especially in Northern Ireland where Jolly Phonics is widely used in schools and reading failure is common.

TbT is an older program, but many of the concepts are surprisingly modern. The phonics taught by TbT is very much in the style of Synthetic Phonics, systematically teaching the code from the sound to the spelling. Instead of a synthetic alphabet like Phono-Graphix or Jolly Phonics, TbT uses 2-page ‘chapters’ dedicated to a single sound or group of related sounds, and methodically builds phonic mapping skills page by page. You can open the book at any page and tell exactly what sounds are being introduced.

TbT often doesn’t express the idea of a mapping clearly, and refers to the ‘sound of the first vowel of “oa”, but these are style issues. The lessons are clear and unambiguous.

TbT also covers some of the ground of Analytic Phonics, teaching across the range of chunk sizes, but correctly starts with smaller chunks and builds them systematically to larger ones. There are no “rules of spelling”.

Keda Cowling, the author of TbT, is a remarkable pioneer. Thinking back when she wrote TbT, there was no such thing as synthetic phonics, no understanding of the problems behind Analytic Phonics. Her stuff worked and other programs didn’t, probably because she had the core ideas right.

Interesting and thorough analysis. Thank you. Are the better phonics methods you describe suitable for teaching dyslexics, many of whom, depending upon the severity of their condition, seem to have difficulty decoding words?

Phonics for a student that struggles with decoding? Yes, absolutely, start as soon as possible. Fixing the phonological deficit is the key step in repairing dyslexia.

An older child (grade 3 and up) needs an intensive, systematic, remedial program, every day. Try the BLENDING program on this website, it is a free and easy to use.

Younger emerging readers are probably better with a more-complete phonics-and-spelling program like Toe-by-Toe.

The big O-G programs work too, they all have some basic phonics. But they are often grotesquely overpriced and tend to be slower because they cover much unnecessary or ineffective material. It’s the phonics that makes the difference, the rest is mostly rubbish.